French Fifth Republic explained — how political power works in France (B2–C1)

France’s Fifth Republic, established in 1958, operates through a unique political system combining presidential power with parliamentary democracy. This semi-presidential system creates a dual executive structure fundamentally different from American or British models, shaping French political life through distinctive institutions, electoral processes, and power-sharing arrangements that continue defining French democracy today.

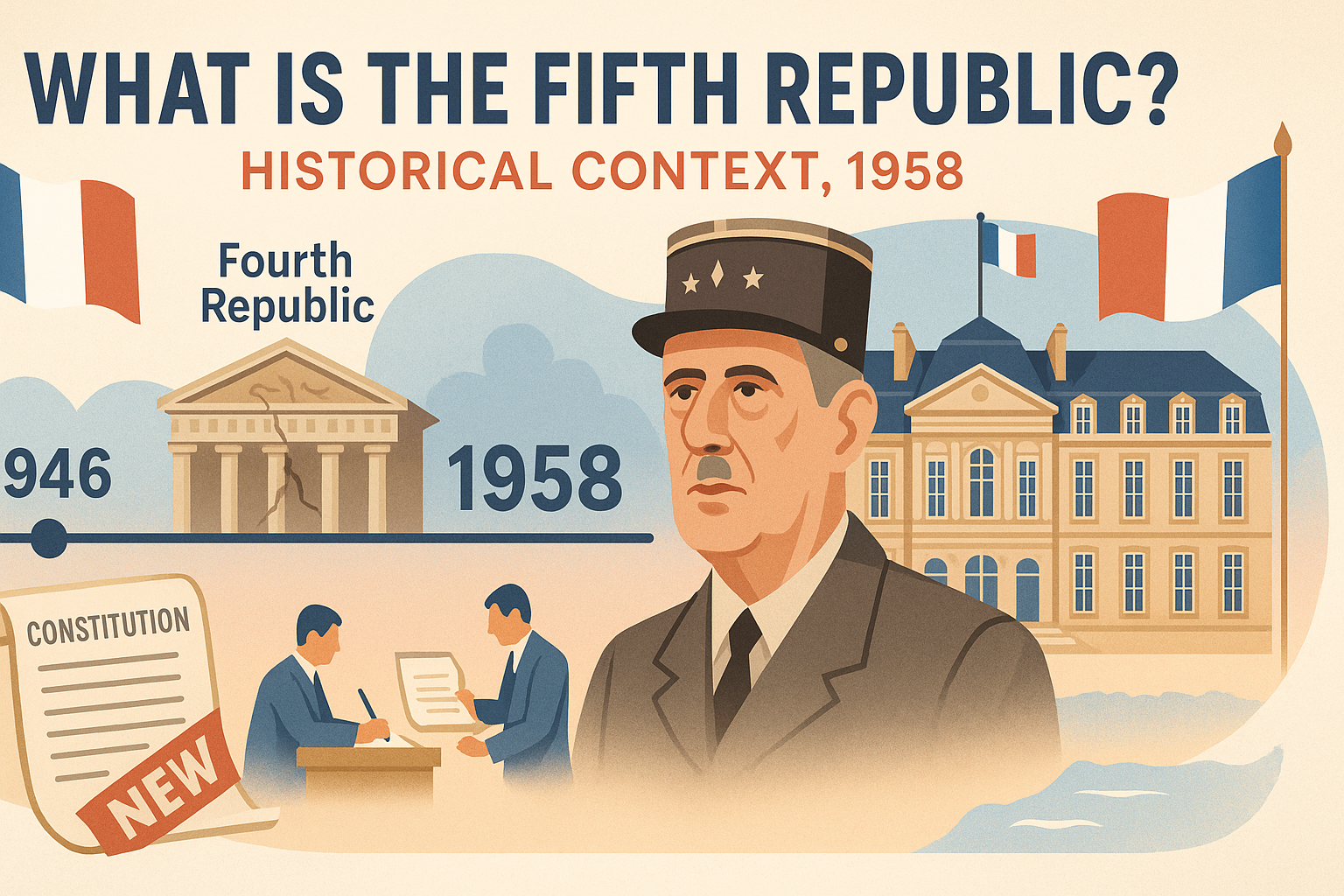

What is the Fifth Republic? Historical context

The Fifth Republic began on October 4, 1958, replacing the unstable Fourth Republic (1946-1958) which collapsed under the Algerian War crisis. General Charles de Gaulle designed this new constitutional system to address the Fourth Republic’s fundamental weakness—excessive parliamentary power producing governmental instability with cabinets falling every few months. Between 1946 and 1958, France cycled through twenty-one governments, creating political paralysis during critical periods including decolonization conflicts.

De Gaulle’s constitutional vision concentrated substantial power in a directly-elected President, creating a “republican monarch” capable of providing stable leadership while maintaining democratic accountability. The 1958 Constitution established this semi-presidential system where executive power divides between President and Prime Minister—a model subsequently adopted by numerous countries but originating uniquely in France’s specific historical circumstances.

The Fifth Republic has proven remarkably durable, surviving sixty-seven years without fundamental constitutional crisis despite significant challenges including May 1968 protests, multiple cohabitation periods, terrorist attacks, and deep political divisions. This stability contrasts sharply with previous French republics’ volatility, validating de Gaulle’s institutional architecture while demonstrating how constitutional design shapes political outcomes.

Executive power — the dual-headed system

Le Président de la République (The President)

Residence: Palais de l’Élysée, Paris

Election: Direct universal suffrage, two-round majority system

Term: Five years (quinquennat), renewable once consecutively since 2008 constitutional reform

Current President: Emmanuel Macron (since May 14, 2017)

Major powers:

- Appoints Prime Minister: Selects PM (usually from parliamentary majority) and approves cabinet ministers

- Foreign policy and defense: Commands armed forces, conducts diplomacy, negotiates treaties

- Dissolution power: Can dissolve Assemblée nationale calling new elections (once per year maximum)

- Referendum power: Can submit questions directly to popular vote

- Emergency powers: Article 16 grants exceptional powers during severe crisis (rarely invoked)

- Appointments: Names senior civil servants, military officers, ambassadors

- Pardon power: Can pardon convicted individuals

Role in practice: The President dominates executive power, setting national agenda, representing France internationally, and functioning as guarantor of national institutions. Often called “republican monarch” due to extensive powers and symbolic stature combining head of state and effective head of government roles.

Le Premier ministre (The Prime Minister)

Residence: Hôtel Matignon, Paris

Appointment: Named by President (not elected), must maintain confidence of Assemblée nationale

Term: No fixed term—serves at President’s discretion or until losing parliamentary confidence

Current Prime Minister: Updates regularly based on political circumstances

Major powers:

- Leads government: Directs cabinet (Conseil des ministres), coordinates ministers

- Legislative process: Proposes laws, manages government’s parliamentary agenda

- Domestic policy: Implements President’s vision, handles day-to-day governance

- Parliamentary accountability: Appears before parliament, answers questions, subject to no-confidence votes

- Regulatory power: Issues decrees and regulations (décrets)

Role in practice: The PM functions as President’s chief executive, translating presidential priorities into concrete policies while managing parliamentary relations. During cohabitation periods (different political camps), PM gains significant autonomy leading domestic policy while President focuses on foreign affairs.

The unique French dual executive

This presidential-parliamentary hybrid creates distinctive power dynamics absent in pure presidential systems (USA) or pure parliamentary systems (UK). The President holds ultimate authority but requires a Prime Minister to implement policies and maintain parliamentary support. This division creates potential for both efficient unified leadership (when President and PM align politically) and democratic power-sharing (during cohabitation).

💡 Key difference from US/UK: Unlike the US President who both symbolizes the nation and runs government, or the UK where Queen symbolizes while PM governs, France splits these roles between President (symbol + strategic direction) and PM (operational governance). Unlike UK’s PM who leads because their party won elections, France’s PM serves because the President appoints them.

Legislative power — the bicameral parliament

L’Assemblée nationale (National Assembly)

Location: Palais Bourbon, Paris

Members: 577 députés (deputies/representatives)

Election: Direct universal suffrage, two-round majority voting by constituency

Term: Five years (renewable indefinitely)

Current composition: Multiple political groups representing left to right spectrum

Major powers:

- Primary legislative chamber: Initiates and votes on laws

- Budget authority: Must approve government budget (Sénat cannot block it)

- Government oversight: Questions ministers, investigates through committees

- No-confidence votes: Can overthrow government (motion de censure) with absolute majority

- Final say: In legislative disagreements with Sénat, Assemblée’s version prevails if government requests

Role in practice: The Assemblée nationale constitutes France’s most powerful legislative body, holding government accountable while exercising decisive legislative authority. Majority control determines whether President enjoys “unified government” or faces opposition requiring compromise.

Le Sénat (The Senate)

Location: Palais du Luxembourg, Paris

Members: 348 sénateurs (senators)

Election: Indirect election by “grands électeurs” (local elected officials) representing territories

Term: Six years, with half renewed every three years (providing continuity)

Current composition: Traditionally center-right majority due to rural overrepresentation

Major powers:

- Legislative review: Examines and amends laws proposed by Assemblée or government

- Territorial representation: Ensures local government interests in national lawmaking

- Constitutional amendments: Equal power with Assemblée for constitutional changes

- Government questioning: Senators question ministers, conduct investigations

- Moderating influence: Provides reflection, expertise, longer-term perspective

Role in practice: The Sénat functions as chamber of reflection, moderating Assemblée’s decisions with territorial perspective and institutional continuity. While less powerful than Assemblée on ordinary legislation, Sénat wields equal authority on constitutional matters and provides important democratic check through different electoral base.

How laws are made — the legislative process

French lawmaking follows a distinctive “navette” (shuttle) process where bills pass between chambers:

- Initiative: Bills proposed by government (projet de loi) or parliament members (proposition de loi)

- First chamber: Examined by relevant committee, debated, amended, voted

- Second chamber: Same process in other chamber

- Navette: If chambers disagree, bill shuttles between them until agreement

- Joint committee: After two readings, government can convene commission mixte paritaire seeking compromise

- Final say: If disagreement persists, government can ask Assemblée for final vote overriding Sénat

- Constitutional review: Constitutional Council reviews if requested before promulgation

- Promulgation: President signs law into force

⚠️ Government’s procedural advantages: The government controls parliamentary agenda through Article 48, can force votes through confidence procedures (Article 49.3), and can prioritize its bills. These tools enable majority governments to pass legislation efficiently but critics argue they reduce parliamentary independence.

The presidential election — how France chooses its leader

The two-round majority system

First round: All qualified candidates compete (minimum 500 signatures from elected officials required). Voters choose freely among all candidates. Victory requires absolute majority (over 50%)—rarely achieved in first round due to multiple candidates.

Second round (two weeks later): Top two candidates from first round face off. Highest vote-getter wins presidency—absolute majority guaranteed with only two options. This runoff ensures President has majority legitimacy.

Why two rounds matter: First round allows voters to support their genuine preference among diverse candidates. Second round forces choice between finalists, creating majority coalition and preventing minority-supported candidates from winning. This system encourages multiple parties while ensuring majoritarian outcome.

Recent presidential elections

2017: Emmanuel Macron (independent centrist) defeated Marine Le Pen (far-right) 66.1% to 33.9% in second round, following first round with four major candidates each receiving 19-24%.

2022: Macron defeated Le Pen again 58.5% to 41.5%, with Jean-Luc Mélenchon (far-left) finishing third in first round at 22%, just missing second-round qualification.

Next election: Scheduled for April-May 2027

Legislative elections and the parliamentary majority

Assemblée nationale elections occur every five years using two-round majority voting within 577 single-member constituencies. Each constituency elects one député through the same two-round logic as presidential elections—majority in first round wins immediately; otherwise, top candidates proceed to second round runoff.

This electoral system heavily favors large parties and coalitions capable of winning majorities in specific districts, disadvantaging smaller parties whose support spreads thinly nationwide. France maintains this system deliberately to produce workable parliamentary majorities rather than proportional fragmentation, though it creates representation distortions where vote percentages don’t match seat allocations.

The synchronization reform

Until 2000, Presidents served seven-year terms while Assemblée served five years, creating frequent misalignment. The 2000 constitutional reform shortened presidential terms to five years matching parliamentary terms. Legislative elections now occur shortly after presidential elections, typically producing aligned majorities as voters reinforce their presidential choice with parliamentary support.

This synchronization reduced cohabitation likelihood but didn’t eliminate it—the 2022 legislative elections denied Macron an absolute majority despite his recent presidential victory, forcing coalition governance without formal cohabitation.

Cohabitation — when political opponents share power

Cohabitation occurs when President and Prime Minister belong to opposing political camps, forcing power-sharing between political rivals. This situation, unique to semi-presidential systems, arises when legislative elections produce a parliamentary majority opposing the President, compelling appointment of an opposition Prime Minister.

Historical cohabitation periods

1986-1988: Socialist President François Mitterrand + Conservative PM Jacques Chirac. First cohabitation revealed system’s flexibility as rivals governed together despite ideological differences. Chirac led domestic policy; Mitterrand focused on foreign affairs and symbolic presidency.

1993-1995: Socialist President Mitterrand + Conservative PM Édouard Balladur. Second cohabitation demonstrated precedent’s sustainability, establishing cohabitation conventions.

1997-2002: Conservative President Chirac + Socialist PM Lionel Jospin. Longest cohabitation resulted from Chirac’s risky decision dissolving Assemblée, which backfired when left won unexpected majority.

💡 Cohabitation dynamics: During cohabitation, the President retains foreign policy and defense preeminence while PM controls domestic agenda. International summits revealed this division—President represents France, but PM handles economic policy negotiations. This power-sharing demonstrated constitutional flexibility while sometimes creating confusion about who spoke for France.

The 2000 reform synchronizing presidential and legislative terms made cohabitation unlikely but not impossible, as 2022 parliamentary results (denying Macron absolute majority) demonstrated that voters can still split their preferences even when elections occur close together.

Key constitutional institutions

Conseil constitutionnel (Constitutional Council)

Members: Nine members serving nine-year terms (three appointed by President, three by Assemblée president, three by Sénat president), plus all living former Presidents

Role: Reviews laws’ constitutionality before promulgation if referred by President, PM, or sixty députés/sénateurs. Since 2008 reform (question prioritaire de constitutionnalité), can review laws’ constitutionality after promulgation when citizens challenge them in court.

Importance: Acts as constitutional guardian, invalidating laws violating constitutional rights. Increasingly important as jurisprudence expands constitutional protection beyond 1958 text to include 1789 Declaration of Rights and 1946 Constitution preamble.

Conseil d’État (Council of State)

Role: Supreme administrative court advising government on legal matters and judging disputes between citizens and state administration

Importance: Protects individual rights against administrative overreach, ensures government respects legal procedures, maintains centuries-old French administrative law tradition distinguishing administrative from ordinary courts.

Local government — decentralization

France divides into thirteen metropolitan regions (plus five overseas), ninety-six départements (plus five overseas), and approximately 35,000 communes (municipalities). This multi-layered local government structure results from gradual decentralization transferring powers from central Paris authority to local elected officials.

The three levels

Régions: Handle economic development, transportation, education (lycées)

Départements: Manage social services, middle schools (collèges), local roads

Communes: Provide local services, urban planning, primary schools, local police

Despite decentralization, France remains more centralized than federal systems like Germany or USA. National government retains significant authority, and Paris’s political, economic, and cultural dominance continues shaping French governance distinctively compared to countries with multiple power centers.

Comparing French and Anglo-American systems

France vs United States

Executive structure: France divides executive between President and PM; USA concentrates it in President alone

Separation of powers: US maintains strict separation with no parliamentary confidence votes; France allows parliament to overthrow government

Legislative power: US Congress more independent from President; French government dominates parliamentary agenda

Electoral system: US Electoral College vs France’s direct popular vote

Federalism: US federal system vs France’s unitary state with decentralization

France vs United Kingdom

Executive: UK PM holds real power with monarch as figurehead; France divides power between President (political but symbolic) and PM (operational)

Constitution: UK unwritten constitution vs France’s rigid written Constitution

Legislature: UK’s House of Commons supreme; France’s Assemblée shares power with President

Electoral system: Similar first-past-the-post for UK parliament vs France’s two-round system

Centralization: Both traditionally centralized, though UK now has devolved parliaments

Current French political landscape

French politics traditionally organized around left-right spectrum, but recent decades witnessed significant realignment. Traditional center-right (Les Républicains) and center-left (Parti Socialiste) parties weakened dramatically, while Emmanuel Macron’s centrist movement (Renaissance, formerly La République En Marche) disrupted conventional alignments.

Major political forces (as of 2024-2025)

Center/Liberal: Renaissance (Macron’s party), MoDem (centrist ally)

Left: La France Insoumise (far-left, Jean-Luc Mélenchon), Parti Socialiste (traditional center-left, weakened), Europe Écologie Les Verts (Greens), Parti Communiste (marginal)

Right: Les Républicains (traditional center-right, weakened), Rassemblement National (far-right, Marine Le Pen), Reconquête (far-right, Éric Zemmour)

This fragmented landscape reflects broader European trends of traditional party decline, populist rise, and voter volatility. Understanding French political dynamics requires following French news sources across political spectrum to grasp diverse perspectives shaping contemporary debates.

Study glossary — political vocabulary

| FR | IPA | EN |

|---|---|---|

| La Cinquième République | /la sɛ̃kjɛm ʁepyblik/ | The Fifth Republic |

| Le Président de la République | /lə pʁezidɑ̃ də la ʁepyblik/ | The President of the Republic |

| Le Premier ministre | /lə pʁəmje ministʁ/ | The Prime Minister |

| L’Assemblée nationale | /lasɑ̃ble nasjɔnal/ | The National Assembly |

| Le Sénat | /lə sena/ | The Senate |

| Un député / Une députée | /œ̃ depyte / yn depyte/ | A representative / deputy |

| Un sénateur / Une sénatrice | /œ̃ senatœʁ / yn senatʁis/ | A senator |

| Le suffrage universel | /lə syfʁaʒ‿ynivɛʁsɛl/ | Universal suffrage |

| Le scrutin | /lə skʁytɛ̃/ | The ballot / voting system |

| Le premier tour | /lə pʁəmje tuʁ/ | First round (election) |

| Le second tour | /lə səɡɔ̃ tuʁ/ | Second round (election) |

| La cohabitation | /la kɔabitasjɔ̃/ | Cohabitation (divided executive) |

| Un projet de loi | /œ̃ pʁɔʒɛ də lwa/ | A government bill |

| Une motion de censure | /yn mɔsjɔ̃ də sɑ̃syʁ/ | A no-confidence motion |

| Le Conseil constitutionnel | /lə kɔ̃sɛj kɔ̃stitysjɔnɛl/ | The Constitutional Council |

| La gauche / La droite | /la ɡoʃ / la dʁwat/ | The left / The right |

| Un parti politique | /œ̃ paʁti pɔlitik/ | A political party |

| La majorité / L’opposition | /la maʒɔʁite / lɔpɔzisjɔ̃/ | The majority / The opposition |