French Subjunctive Made Simple for English Speakers (B1-B2)

You’re practicing French with a conversation partner, feeling confident about your grammar, when you say “Je veux que tu viens demain” (I want that you come tomorrow) and your partner gently corrects: “No, it’s ‘que tu viennes’—you need the subjunctive after ‘je veux que.'” You stare blankly. Subjunctive? You vaguely remember your textbook mentioning something called the subjunctive months ago in a chapter you skipped because it looked terrifying, but now you’re confronted with the reality that French uses an entire grammatical mood—not just a tense, a whole mood—that doesn’t exist in modern English and that apparently changes how you conjugate verbs in ways you haven’t learned yet. The French subjunctive represents the point where many English speakers’ French progress stalls because it requires learning both a new concept (expressing doubt, emotion, and necessity through verb forms rather than separate words) and new conjugations for every verb you already know, triggered by phrases that seem arbitrary until you understand the underlying logic. Americans and British learners struggle particularly hard with the subjunctive because English eliminated most subjunctive forms centuries ago—we say “I insist that he come” using subjunctive only in the most formal registers, and most English speakers don’t even recognize this as grammatically different from “he comes.” This guide explains the French subjunctive with the practical patterns, essential conjugations, and mental models Roger teaches students in his lessons—the knowledge that transforms the subjunctive from incomprehensible nightmare into a learnable system with predictable rules you can actually apply.

What the subjunctive actually is (and why English speakers don’t recognize it)

The first obstacle to understanding the French subjunctive is that English speakers don’t have the conceptual framework for it. When your textbook says “the subjunctive expresses doubt, emotion, necessity, and possibility,” English speakers nod along while thinking “I already express doubt, emotion, necessity, and possibility in English—I say ‘I might go,’ ‘I want him to come,’ ‘it’s necessary that she understand.’ What’s different in French?”

The difference: in English, you express these concepts through separate words (might, want, necessary) while keeping the main verb unchanged. In French, you express these concepts by changing the verb itself into subjunctive form. The doubt, emotion, or necessity gets embedded into the verb conjugation rather than staying in separate words:

🇺🇸 It’s necessary that I be there at eight o’clock (rare English subjunctive “be” instead of “am”)

Notice that formal English would say “that I be there” not “that I am there”—this is actually English subjunctive, but it’s so rare that most English speakers would say “that I’m there” and never notice they’re technically breaking formal grammar rules. French makes this distinction mandatory and uses it constantly.

Roger learned the subjunctive during his university linguistics courses in London, which gave him theoretical understanding, but when he moved to France in 2012, he discovered that knowing the subjunctive exists and actually using it correctly in conversation are completely different skills. The breakthrough came when his French colleague explained: “The subjunctive is the verb form you use when you’re talking about things that aren’t certain reality—they’re wishes, doubts, emotions, or requirements, not facts.”

This distinction between “certain reality” (indicative mood) and “uncertain/subjective reality” (subjunctive mood) governs when French uses each mood:

🇺🇸 I know that he’s coming tomorrow (indicative—certain fact)

🇺🇸 I doubt that he’s coming tomorrow (subjunctive—uncertain, doubted)

The verb “venir” appears as “vient” (indicative) when certain, “vienne” (subjunctive) when doubted. English uses the same form “is coming” in both sentences, expressing the difference through “know” vs. “doubt” rather than through the verb itself.

The magic word “que” and the two-subject rule

Before you even worry about subjunctive conjugations, you need to recognize when the subjunctive is required structurally. Roger teaches students in his lessons a simple diagnostic: the subjunctive almost always appears after “que” (that) when two different subjects are involved—the person who wants/doubts/feels something, and the person who will do something.

When you say “I want to go,” there’s only one subject (I), so you use the infinitive in French:

🇺🇸 I want to leave (one subject = infinitive, no subjunctive)

But when you say “I want you to go,” there are two subjects (I want, you go), and French requires “que” + subjunctive:

🇺🇸 I want that you leave / I want you to leave (two subjects = que + subjunctive)

This two-subject construction with “que” is where the subjunctive lives. English handles this with infinitives (“I want you to leave”), but French needs the subjunctive structure. Recognizing this pattern helps you anticipate when you’ll need subjunctive before you even think about conjugation.

Essential Subjunctive Trigger Phrases (Learn These First)

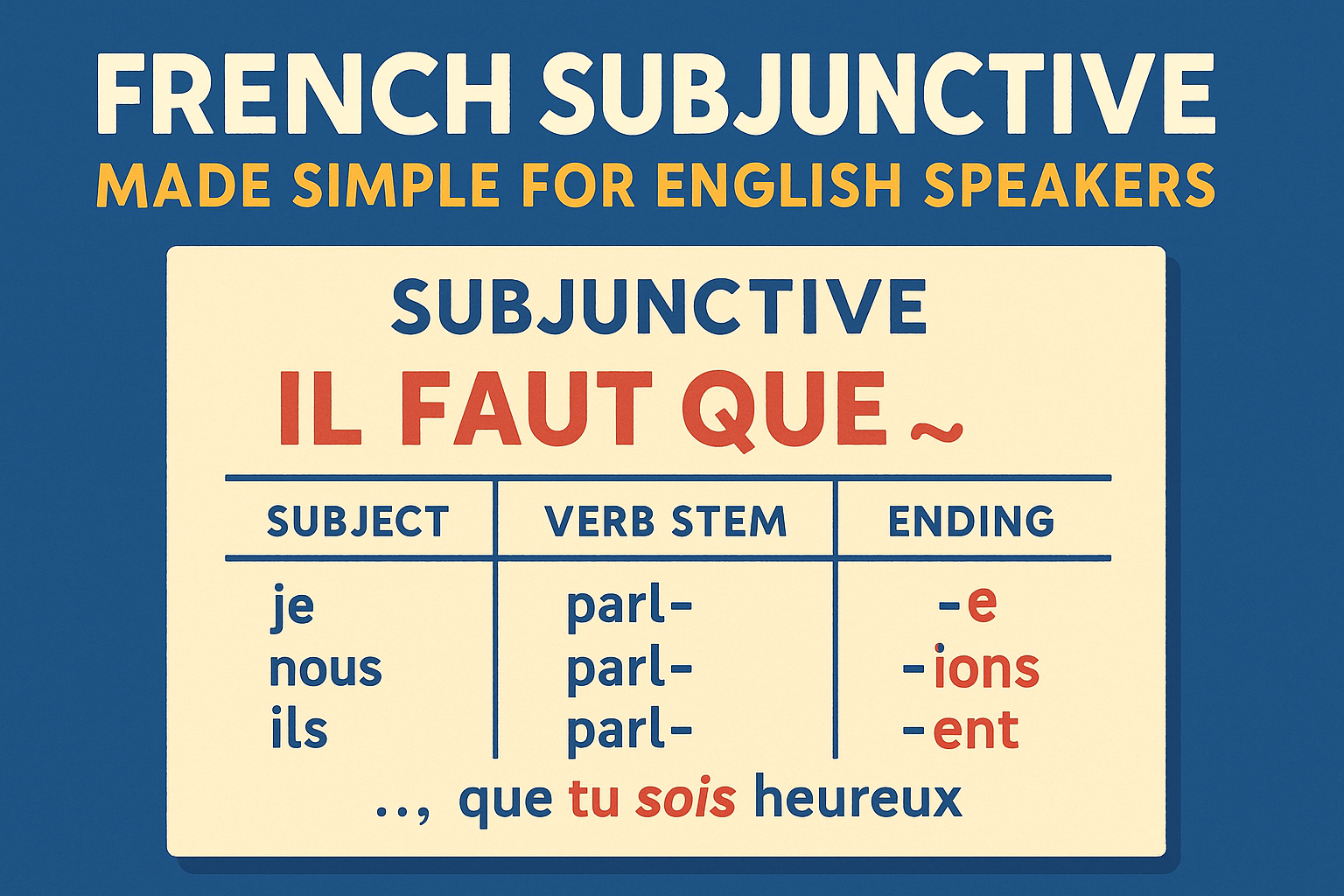

NECESSITY & OBLIGATION (Il faut que + subjunctive)

🇺🇸 I have to go to work / It’s necessary that I go to work

🇺🇸 You have to do your homework / It’s necessary that you do your homework

DESIRE & PREFERENCE (Vouloir que, aimer que, préférer que + subjunctive)

🇺🇸 I want you to come with me

🇺🇸 I would like you to be there

EMOTION (Être content que, avoir peur que, regretter que + subjunctive)

🇺🇸 I’m happy that you succeeded

🇺🇸 I’m afraid that he’s sick

DOUBT & UNCERTAINTY (Douter que, ne pas penser que + subjunctive)

🇺🇸 I doubt that he can come

🇺🇸 I don’t think that she wants to leave

CONCESSION (Bien que, quoique, sans que + subjunctive)

🇺🇸 Although it’s late, we can continue

🇺🇸 I’m leaving without him knowing

IMPERSONAL EXPRESSIONS (Il est important que, il est possible que + subjunctive)

🇺🇸 It’s important that you understand

🇺🇸 It’s possible that she’ll arrive late

The four essential subjunctive conjugations you must memorize

Learning every subjunctive conjugation for every verb overwhelms beginners and isn’t necessary initially. Roger’s approach: master the subjunctive forms of four irregular verbs that appear constantly—être, avoir, faire, and aller. These four verbs account for probably 60% of subjunctive usage in everyday French, and once you know these, you can function conversationally while gradually learning other forms.

The verb “être” (to be) is the most irregular and most essential:

🇺🇸 I have to be patient (subjunctive: je sois, not je suis)

🇺🇸 You have to be there (subjunctive: tu sois)

🇺🇸 He has to be ready (subjunctive: il soit)

The verb “avoir” (to have) is equally critical:

🇺🇸 I want you to have more confidence (subjunctive: tu aies, not tu as)

🇺🇸 We need to have time (subjunctive: nous ayons)

The verb “faire” (to do/make) appears in countless expressions:

🇺🇸 I have to pay attention (subjunctive: je fasse, not je fais)

🇺🇸 I want you to do your homework (subjunctive: tu fasses)

The verb “aller” (to go) is one of the most common verbs in French:

🇺🇸 I have to go to the doctor (subjunctive: j’aille, not je vais)

🇺🇸 I want her to go to university (subjunctive: elle aille)

Roger drills these four verbs extensively in his lessons because students who can use these subjunctive forms automatically can handle 60-70% of conversational situations requiring subjunctive. The remaining verbs can be learned gradually as you encounter them.

💡 Roger’s subjunctive learning progression

Roger developed this step-by-step approach after watching students try to learn all subjunctive forms simultaneously and become overwhelmed. This progression builds competence gradually:

Week 1: Recognition only (don’t produce yet)

- Learn to recognize “Il faut que” and “Je veux que” as subjunctive triggers

- When you hear subjunctive forms, notice they’re different from indicative

- Don’t try to produce subjunctive yet—just recognize it exists

- Listen to French conversations and mark every time you hear “que” + different verb

Week 2-3: Master the big four verbs (être, avoir, faire, aller)

- Memorize subjunctive conjugations for these four verbs only

- Practice: “Il faut que je…” with all four verbs daily

- Create your own sentences: “Il faut que je sois…”, “Il faut que j’aie…”, “Il faut que je fasse…”, “Il faut que j’aille…”

- Goal: automatic production of these four verbs in subjunctive after “il faut que”

Week 4: Expand to “je veux que” + the big four

- Practice: “Je veux que tu…” with être, avoir, faire, aller

- Combine necessity and desire triggers with the four essential verbs

- Start noticing these constructions in native speech

Week 5-6: Add emotion triggers (être content que, avoir peur que)

- Same four verbs, new triggers

- “Je suis content que tu sois là”, “J’ai peur qu’il aille trop vite”

- Pattern recognition: emotion + que = subjunctive

Week 7+: Gradually add regular -er, -ir, -re verb subjunctive forms

- Learn that most regular verbs follow predictable patterns

- Add 2-3 new verb subjunctive forms per week

- Priority: verbs you use most often in conversation

This progression takes 2-3 months but builds solid subjunctive competence without overwhelming cognitive load. Students report that mastering the big four first makes everything else easier because you understand the concept before tackling hundreds of conjugations.

When NOT to use the subjunctive: the certainty test

English speakers make a predictable error: overusing the subjunctive because they’ve learned trigger phrases but haven’t internalized the certainty principle. Not every verb after “que” requires subjunctive—only those expressing doubt, emotion, necessity, or possibility. Verbs expressing certainty, knowledge, or declaration use normal indicative mood.

The critical distinction appears with verbs of thinking and saying:

🇺🇸 I think that he’s coming tomorrow (indicative—you believe it’s true)

🇺🇸 I don’t think that he’s coming tomorrow (subjunctive—you doubt it)

Positive “je pense que” expresses belief/certainty, so it takes indicative. Negative “je ne pense pas que” expresses doubt, so it takes subjunctive. This logical distinction makes sense once you understand the certainty principle, but English speakers initially find it arbitrary because English uses identical constructions for both.

Similarly, “je sais que” (I know that) always takes indicative because knowledge represents certainty:

🇺🇸 I know that he’s there (indicative “est”, never subjunctive—knowledge is certain)

But “je doute que” (I doubt that) takes subjunctive because doubt is uncertainty:

🇺🇸 I doubt that he’s there (subjunctive “soit”—doubt requires subjunctive)

Roger teaches the certainty test: ask yourself “Am I expressing something I’m certain about (fact, knowledge, declaration) or something uncertain (doubt, desire, emotion, necessity)?” Certain = indicative. Uncertain = subjunctive.

⚠️ The “espérer que” exception that confuses everyone

The verb “espérer” (to hope) logically seems like it should take subjunctive—hoping is about uncertain future events, desires, things that might not happen. But French grammar treats “espérer que” as taking indicative, not subjunctive:

🇺🇸 I hope that he will come (indicative “viendra”, NOT subjunctive)

Why this exception? Because “espérer” etymologically relates to expectation rather than pure wish—when you hope for something in French, you’re expressing optimistic expectation (closer to certainty) rather than pure desire. This is one of the few major exceptions to the certainty rule.

Compare with “souhaiter” (to wish), which DOES take subjunctive:

🇺🇸 I wish that he would come (subjunctive “vienne”)

Students hate this exception because it seems illogical. Roger’s advice: just memorize “espérer que + indicative” as a special case and move on—spending mental energy trying to understand the logic yields diminishing returns.

Building subjunctive fluency through pattern practice

The subjunctive becomes automatic through repeated pattern practice with the same trigger phrases combined with essential verbs. Roger’s trilingual background taught him that grammar rules need to become unconscious habits, not conscious calculations. When a French person says “Il faut que je…”, the subjunctive form appears automatically because they’ve used this construction thousands of times—they’re not consciously thinking “necessity requires subjunctive.”

The practice method that works: take one trigger phrase (like “Il faut que”) and combine it with the four essential verbs (être, avoir, faire, aller) across all subjects (je, tu, il/elle, nous, vous, ils/elles). Say these combinations out loud until they feel automatic:

🇺🇸 I/you/he/we/you(pl)/they have to be (drilling pattern until automatic)

Then take the same verb through different trigger phrases:

🇺🇸 Necessity / desire / emotion—same verb, different triggers

This drilling feels tedious but builds the neural pathways that make subjunctive automatic. Native speakers acquired these patterns through thousands of repetitions as children; adult learners must replicate this exposure deliberately through focused practice.

Roger assigns students specific daily practice: create three sentences using “Il faut que” + être/avoir/faire/aller. Write them, say them aloud, use them in conversation if possible. After two weeks of this daily practice, students report that “Il faut que je sois” starts appearing automatically without conscious thought—exactly the goal.

Study glossary – French subjunctive vocabulary

| French Term | English Translation | Usage Example |

|---|---|---|

| Le subjonctif | The subjunctive (mood) | On utilise le subjonctif après “il faut que” |

| Il faut que | It’s necessary that / One must | Il faut que tu viennes |

| Je veux que | I want that | Je veux que tu sois là |

| Bien que | Although | Bien qu’il soit tard |

| Je doute que | I doubt that | Je doute qu’il puisse venir |

| Je suis content que | I’m happy that | Je suis content que tu aies réussi |

| J’ai peur que | I’m afraid that | J’ai peur qu’elle soit malade |

| Il est possible que | It’s possible that | Il est possible qu’il pleuve |

| Avant que | Before | Avant qu’il parte |

| Sans que | Without | Sans que je le sache |

| Pour que | So that / In order that | Pour que tu comprennes |

| Jusqu’à ce que | Until | Jusqu’à ce qu’il arrive |

From fear to fluency: embracing the subjunctive

The subjunctive’s reputation as impossible French grammar intimidates learners unnecessarily. Yes, it’s complex. Yes, English doesn’t prepare you for it. Yes, learning all the conjugations takes time. But the subjunctive follows predictable rules once you understand the certainty principle, and most everyday French uses the same dozen trigger phrases repeatedly with a limited set of common verbs.

Roger emphasizes in his lessons that students who master the big four verbs (être, avoir, faire, aller) in subjunctive can handle most conversational situations requiring subjunctive. You don’t need perfect command of every verb’s subjunctive form to communicate effectively—you need automatic command of the most frequent combinations that appear daily.

The subjunctive represents advanced French grammar, typically introduced at B1 level and mastered gradually through B2 and C1. Don’t expect instant fluency. Native French children make subjunctive errors until age 10-12, and they’re acquiring it through constant immersion. Adult learners using deliberate practice can achieve functional subjunctive competence in 2-3 months of focused study, with full mastery developing over 1-2 years of continued use.

The psychological shift that helps: stop viewing the subjunctive as arbitrary French complication and start viewing it as elegant grammatical expression of uncertainty, emotion, and necessity through verb forms rather than separate words. French embeds these concepts into verbs; English keeps them separate. Neither approach is superior—they’re simply different solutions to the same communicative challenge. Understanding this helps you appreciate the subjunctive rather than resenting it.

Start with recognition before production, master the four essential verbs before expanding, drill trigger phrases until automatic, and practice daily through deliberate sentence creation. The subjunctive becomes less terrifying with every successful use, and the moment you first use “Il faut que je sois” correctly in conversation without thinking about it consciously, you’ll know you’re developing real French fluency beyond basic communication into sophisticated expression that marks advanced speakers.