Why French People Don’t Smile at Strangers: Cultural Guide (A2-B2)

You board the Paris metro at 8 AM, surrounded by commuters heading to work. Coming from California where you smile at everyone as basic friendliness, you make eye contact with the woman sitting across from you and give her a warm, genuine smile. She immediately looks away uncomfortably, her face registering something between confusion and alarm. You try again with the man standing next to you—same result. By the third attempt, you’re wondering if you have something on your face or if Parisians are simply the coldest people on earth. The truth: you’re performing American friendliness in a culture where smiling at strangers reads as bizarre, potentially threatening, or suspiciously insincere behavior. American culture teaches that smiling at strangers is polite, warm, and signals harmless friendliness—the more you smile, the nicer you are. French culture teaches that smiling without reason at people you don’t know is fake, possibly manipulative, or indicates you want something from them, and genuine smiles should be reserved for actual positive emotions directed at people you actually have relationships with. This fundamental difference in what smiles mean creates one of the biggest cultural misunderstandings between French and Americans, where each group thinks the other is rude for opposite reasons. This guide explains the cultural psychology behind French non-smiling with the context and vocabulary Roger teaches students in his lessons—the knowledge that helps you understand French facial expressions without feeling personally rejected.

What smiles mean in American versus French culture

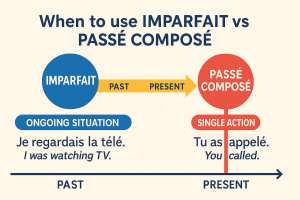

The smile gap between American and French culture stems from fundamentally different beliefs about what facial expressions should communicate. Americans learn from childhood that smiling is polite behavior you perform to make others comfortable, signal you’re friendly and safe, and smooth social interactions. The smile becomes a social tool you deploy strategically—smile at your boss, smile at customers, smile at strangers on the street to show you’re a good person who means no harm.

French culture teaches the opposite: your facial expression should reflect your genuine emotional state, and performing emotions you don’t feel is dishonest. If you’re not experiencing positive emotion, why would you smile? Smiling at strangers you have no relationship with and no genuine positive feelings toward reads as fake, manipulative (what do you want from me?), or possibly unstable (why is this person grinning at everyone?).

When Roger first moved to Paris in 2012, his British background gave him some preparation—British culture falls between American enthusiasm and French reserve. But even British people smile more than French people in public spaces. Roger remembers walking through his neighborhood, smiling politely at neighbors as he would in London, and receiving nothing but blank stares or averted eyes. One neighbor finally asked if something was wrong because he seemed “too happy” all the time—in French culture, constant smiling suggested either tourist naiveté or possible mental instability, not friendliness.

The linguistic difference reveals the cultural divide. In French, when someone asks why you’re smiling, the expected answer involves a reason:

🇺🇸 Why are you smiling? (expects genuine reason, not “just being friendly”)

🇺🇸 I’m smiling because I’m happy (smile requires emotional justification)

Americans asked “why are you smiling?” might answer “just being friendly!” or “no reason!” These answers sound nonsensical to French people—smiling without reason is precisely what seems fake or strange. The smile should indicate actual internal emotional state, not performed social niceness.

The neutral face as default French expression

Walk down any street in Paris, Lyon, or Marseille during morning commute hours and you’ll see hundreds of faces displaying what Americans call “resting bitch face”—a neutral or slightly serious expression that Americans interpret as angry, sad, or unfriendly. French people call this “le visage neutre” (the neutral face), and it’s simply the default expression when you’re not experiencing strong emotions worth displaying publicly.

The neutral face doesn’t mean French people are unhappy or hostile. It means they’re going about their day in a normal mental state that doesn’t warrant smiling. They’re thinking about work, planning their evening, wondering what to make for dinner, existing in the ordinary mental space that most humans occupy most of the time—and French culture doesn’t require performing happiness during ordinary existence.

Americans uncomfortable with this neutral face often describe French people as looking “mean” or “cold.” But French people experiencing the same internal state as neutral-faced French people—neither particularly happy nor sad, just existing—feel compelled to smile constantly because American culture frames the neutral face as rude or unwelcoming. This creates genuine exhaustion: performing constant low-level happiness for strangers is emotionally draining work.

Roger teaches students in his lessons that adopting the French neutral face feels liberating once you accept that you don’t owe strangers emotional performance. You can simply exist in public spaces without managing your facial expression to make others comfortable. The elderly French woman on the metro with a serious expression isn’t judging you or disliking you—she’s just riding the metro with her normal face, the same way she’d look sitting alone in her living room.

What French Facial Expressions Actually Mean

The Neutral Face (le visage neutre):

American interpretation: Angry, sad, unfriendly, judgmental

French meaning: Normal default state, not experiencing strong emotions, just existing

When displayed: Public transportation, walking streets, shopping, waiting in lines

The Brief Eye Contact Without Smile:

American interpretation: Rude acknowledgment, dismissive

French meaning: Polite acknowledgment of presence without creating relationship

When displayed: Passing someone in hallway, sitting down near someone, brief unavoidable encounters

The Slight Smile (le petit sourire):

American interpretation: Bare minimum politeness, cold

French meaning: Genuine but restrained positive acknowledgment, appropriate for acquaintances

When displayed: Greeting neighbors you know slightly, acknowledging regular shopkeepers, polite encounters

The Genuine Smile (le sourire authentique):

American interpretation: Finally, normal friendliness!

French meaning: Actual positive emotion, reserved for friends, family, genuinely amusing situations

When displayed: With friends and family, when something actually amusing happens, genuine pleasure

The Constant American Smile:

American interpretation: Friendly, approachable, polite, warm

French interpretation: Fake, suspicious, possibly mentally unstable, wanting something, salesperson mode

French reaction: Discomfort, avoidance, wondering what you want from them

Service workers and the expectation gap

Americans visiting France consistently complain about rude service workers—waiters who don’t smile, cashiers who seem annoyed by customers, hotel staff who maintain professional distance rather than enthusiastic friendliness. The service culture gap creates more friction than almost any other aspect of French-American cultural difference.

In America, service workers are expected to perform enthusiastic friendliness regardless of actual emotional state. The waitress with a sick child at home and bills she can’t pay must still smile warmly, ask “how are you folks doing today?” with apparent genuine interest, and maintain cheerful banter throughout your meal. This emotional labor is mandated—workers who don’t smile get complaints, poor tips, or fired.

In France, service workers are expected to be competent, efficient, and professionally polite. Smiling is neither required nor expected. A waiter who takes your order accurately, brings your food promptly, and responds to requests efficiently is doing their job perfectly—whether they smile or not is irrelevant to job performance. The neutral professional face is standard, and forcing workers to perform fake happiness would be considered degrading:

🇺🇸 The server was very professional (compliment, no mention of smiling needed)

🇺🇸 She did her job correctly (sufficient praise, smiling not part of job requirements)

When Americans complain that French service workers are rude, they’re usually describing workers who are being perfectly polite by French standards—just not performing American emotional labor. The baker who efficiently hands you bread without smiling isn’t being rude; she’s being professional. The museum ticket seller who remains neutral-faced while processing your transaction is doing exactly what the job requires.

Roger experienced this reversed when visiting American friends after living in France. American service workers’ constant smiling and enthusiastic small talk felt overwhelming and intrusive—he found himself wondering what they wanted from him, since French culture associates constant smiling with sales manipulation. The cultural recalibration works both directions.

⚠️ The tipping connection Americans miss

American service workers’ mandatory smiling connects directly to tip culture. Servers who depend on tips for survival must perform friendliness to maximize income—the smile is literally part of earning a living wage. French service workers receive actual salaries and don’t depend on tips for survival (tips are small bonuses for exceptional service, not payment for standard service).

This means French servers have no financial incentive to perform fake happiness. They can be professionally neutral without losing income. Americans expecting tip-culture emotional performance from French workers who aren’t in tip-dependent positions are imposing inappropriate cultural expectations.

When Americans say “the service would be better if they smiled more,” they’re revealing they value emotional performance over actual competence. French people would say “the service would be better if it was faster and more accurate”—smiling is irrelevant to service quality.

When French people do smile: The contexts that matter

French people aren’t emotionless robots incapable of smiling—they smile frequently and warmly in appropriate contexts. Understanding when French people smile reveals the logic of French emotional expression: smiles should reflect genuine positive emotions directed at people you have actual relationships with.

French people smile broadly and genuinely with friends and family. The reserved person who maintained a neutral face on the metro transforms completely when greeting a friend for dinner—kisses on both cheeks (la bise), genuine warm smiles, animated conversation. The difference is relationship: these are people the French person actually knows and cares about, so genuine positive emotions warrant genuine smiles.

French people smile when something is actually amusing. A genuinely funny joke, a child doing something cute, a ridiculous situation that’s objectively humorous—these produce authentic smiles because the emotion is real. The smile indicates “this is amusing” rather than performing “I am a friendly person.” The difference matters: the smile points to the situation, not to self-presentation.

French people smile during genuine positive interactions with acquaintances. When you’ve been buying bread from the same boulangerie for six months and the baker recognizes you, she might smile slightly when you enter because you’ve developed a real (though minor) relationship. This smile reflects actual recognition and mild positive feeling, not performed friendliness toward a stranger:

🇺🇸 Ah hello, the usual? (slight smile acknowledging regular customer relationship)

French people smile when receiving good news, experiencing pleasant surprises, or enjoying genuinely positive moments. These smiles are unguarded and authentic because they reflect actual internal emotional states, not social performance. A French person learning they got the job they wanted smiles enormously—not because they’re “finally being nice” but because they’re experiencing genuine joy worth displaying.

What French people don’t do: smile at random strangers for no reason, maintain constant low-level smiling as default expression, or perform friendliness for people they have no relationship with. These behaviors read as fake, suspicious, or strange rather than polite.

The American smile as cultural aggression

Americans rarely consider that their constant smiling might make others uncomfortable—in American culture, smiling is unambiguously positive, and more smiling is always better. But in French culture, American-style smiling at strangers can read as invasive, demanding inappropriate intimacy, or even threatening.

When an American smiles warmly at a French stranger on the metro, the French person’s internal monologue goes something like: “Why is this stranger smiling at me? What do they want? Are they trying to sell me something? Are they about to ask me for money? Are they mentally unstable? Should I move to another seat?” The smile that Americans intend as friendly creates genuine discomfort and mild alarm.

French people, particularly French women, sometimes interpret American smiling as unwanted romantic or sexual interest. In French culture, sustained eye contact with a smile signals potential romantic interest. American men who smile at French women thinking they’re just being friendly might be unintentionally communicating sexual interest, creating uncomfortable situations where the woman now has to figure out how to reject an advance that wasn’t consciously being made.

The sustained smile also creates obligation that French people resent. When you smile at someone, French social logic suggests you want something from them—information, help, to start a conversation. This creates pressure to respond, engage, or provide whatever you’re nonverbally requesting. Americans smiling “for no reason” violate this logic, creating confusion about what response is appropriate.

Roger experienced this reversed in his lessons with American students who couldn’t understand why their friendly smiling seemed to make French people uncomfortable. The breakthrough came when he explained: “Imagine someone you don’t know walking up to you and staring intensely into your eyes while grinning. That’s how your ‘friendly smile’ feels to French people—not friendly, intrusive.”

💡 Roger’s facial expression adaptation strategy

Roger developed this system for helping American students adjust their facial expressions for French contexts without feeling like they’re becoming cold or unfriendly:

Phase 1: Awareness (Days 1-7)

- Notice how often you smile at strangers in a typical day

- Observe French people’s faces in public spaces—really look at the neutral expression

- Recognize that most French faces aren’t angry, just neutral

- Stop interpreting neutral faces as personal rejection

Phase 2: Reduction (Days 8-21)

- Consciously reduce smiling at strangers by 80%

- Maintain neutral face on public transportation (no smiling at seatmates)

- Stop smiling at service workers before they acknowledge you

- Reserve smiles for people who’ve already engaged with you

- Notice the relief of not having to perform constant friendliness

Phase 3: Calibration (Days 22+)

- Smile genuinely when something is actually amusing or pleasant

- Return smiles from people you’ve developed relationships with (regular baker, neighbor)

- Use slight smiles during polite interactions that warrant positive acknowledgment

- Maintain neutral face as comfortable default in public spaces

- Experience the cultural shift where genuine smiles mean more because they’re rarer

Students report that after 3-4 weeks, the neutral face feels natural and comfortable rather than forced or rude. They also report that their genuine smiles carry more meaning because they’re no longer performing constant background friendliness.

The intelligence and authenticity connection

One aspect of French non-smiling culture that Americans rarely understand: in French cultural psychology, constant smiling suggests either low intelligence or manipulative insincerity. This harsh judgment stems from French cultural values that prize intellectual seriousness, authentic emotional expression, and skepticism of surface appearances.

French culture associates intelligence with being able to see the complexity, difficulty, and tragedy in life. Someone who smiles constantly despite living in a world with poverty, injustice, environmental crisis, and human suffering either doesn’t understand reality (stupid) or is pretending not to see it (fake). Intellectual seriousness requires acknowledging that life contains significant problems worth being serious about.

Americans value optimism and positive thinking as virtues—the ability to smile despite difficulties signals resilience and mental health. French people view this same behavior as denial or superficiality—refusing to acknowledge reality because facing it would be uncomfortable. The person who can examine life honestly and still smile must have genuine reason for that smile; otherwise, they’re performing optimism rather than experiencing it.

The authenticity dimension matters equally. French culture deeply values being “vrai” (true/genuine) and despises being “faux” (false/fake). Performing emotions you don’t feel for social purposes is quintessentially faux behavior. Americans who smile when they’re not happy, laugh at jokes that aren’t funny, and perform enthusiasm they don’t feel are being systematically dishonest about their internal states—which French culture considers moral failure.

This creates fascinating mirror judgments: Americans think French people are rude for not performing friendliness; French people think Americans are fake for performing friendliness they don’t genuinely feel. Each group is judging the other by their own cultural values and finding the other wanting.

Study glossary – French facial expression vocabulary

| French Term | English Translation | Usage Example |

|---|---|---|

| Sourire | To smile / A smile | Elle a un beau sourire |

| Le visage neutre | The neutral face | Il garde un visage neutre |

| Faire semblant | To pretend / To fake | Il fait semblant d’être content |

| Être vrai(e) | To be genuine/authentic | Elle est vraie, pas fausse |

| Être faux/fausse | To be fake/false | Ce sourire est faux |

| L’expression du visage | Facial expression | Son expression du visage était neutre |

| Avoir l’air | To look/seem | Tu as l’air content aujourd’hui |

| Rester sérieux/sérieuse | To remain serious | Il reste sérieux même quand il plaisante |

| L’émotion authentique | Genuine emotion | C’est une émotion authentique |

| La politesse | Politeness | La politesse n’exige pas de sourire |

| Le contact visuel | Eye contact | Éviter le contact visuel dans le métro |

| Être réservé(e) | To be reserved | Les Français sont plus réservés en public |

Learning to read French faces without American assumptions

The key to navigating French non-smiling culture isn’t forcing yourself to smile less (though that helps)—it’s learning to read French facial expressions and social cues without filtering them through American cultural assumptions. A neutral French face doesn’t mean what a neutral American face means; the same expression carries different social meaning in different cultural contexts.

When Roger works with students in his lessons, the biggest breakthrough comes when Americans stop interpreting French neutral faces as rejection or hostility. The metro passenger not smiling at you isn’t judging you negatively—they literally aren’t thinking about you at all. You’re part of the scenery, same as the advertisements and the metro map. This anonymity in public spaces is comfortable to French people and feels cold to Americans who expect low-level friendly acknowledgment from everyone.

The subtle French social cues that indicate warmth or coldness operate differently than American cues. A slight softening around the eyes without an actual smile can indicate genuine warmth—French people don’t need to deploy their whole face to signal positive regard. A brief nod of acknowledgment carries more weight than American nodding because French people don’t nod at everyone constantly. When a French person chooses to acknowledge you specifically, that choice matters.

French politeness doesn’t require smiling, but it does require verbal respect markers—”bonjour,” “s’il vous plaît,” “merci,” “au revoir.” An unsmiling shopkeeper who uses all these phrases is being perfectly polite by French standards. An American who smiles warmly but skips “bonjour” is being rude by French standards. The verbal politeness system matters more than facial expressions in determining whether someone is polite or rude.

Understanding this helps Americans navigate a crucial reality: you can have warm, genuine, deep relationships with French people who rarely smile at you in American-style enthusiastic ways. French friendship operates through different signals—time invested, intellectual engagement, willingness to help, loyalty over years—not through constant smiling and verbal enthusiasm. The friend who maintains a neutral face while listening to your problems but then spends three hours helping you solve them is showing profound French friendship, even if an American might read the neutral face as disinterest.

The adaptation Americans need to make isn’t becoming cold or unfriendly—it’s separating smiling from friendliness in their internal cultural logic. Friendliness can exist without constant smiling. Warmth can be genuine without performed enthusiasm. Connection can be deep without emotional exhibition. French culture operates on all these principles, and understanding them allows Americans to access French warmth that exists in different forms than American warmth.