Imparfait vs Passé Composé Explained: Timeline Method (B1-B2)

You’re telling a French colleague about your childhood, enthusiastically describing how you lived in the countryside, played in the fields every day, and loved animals—and you say “J’ai habité à la campagne, j’ai joué dans les champs, et j’ai aimé les animaux,” using passé composé throughout because English taught you that past tense is past tense. Your colleague listens politely but then gently corrects: “Actually, for ongoing states and habitual actions in the past, we use imparfait—’j’habitais à la campagne, je jouais dans les champs, j’aimais les animaux.'” You stare blankly, wondering what imparfait even is and why French needs two completely different past tenses when English makes do with simple past for everything. The imparfait versus passé composé distinction represents one of the most frustrating grammar hurdles for English speakers because English collapsed this distinction centuries ago, using “I lived,” “I was living,” and “I used to live” interchangeably with one simple past form, while French maintains a rigid grammatical separation based on whether past actions were completed events (passé composé) or ongoing background states (imparfait). This guide explains the timeline visualization method Roger teaches in his lessons—the mental model that transforms this abstract grammar rule into an intuitive decision you can make while speaking French.

Why English doesn’t prepare you for this distinction

When Roger first studied French at university in London, the imparfait versus passé composé chapter nearly defeated him. His textbook explained: “Use passé composé for completed actions in the past, imparfait for ongoing actions or habitual past actions.” This seemed logical in theory, but when Roger tried to apply it to actual sentences, he discovered that English gives zero guidance for making this distinction because English uses identical forms for both concepts.

Consider the English sentence “I was tired yesterday.” This could translate to French as either “J’étais fatigué hier” (imparfait—describing ongoing state) or “J’ai été fatigué hier” (passé composé—describing a temporary completed condition), depending on subtle contextual meaning that English doesn’t distinguish grammatically. English speakers don’t consciously process this difference because our language doesn’t force us to choose.

The fundamental conceptual divide: passé composé treats past actions like discrete events that happened and ended—think of them as snapshots or photographs capturing specific moments. Imparfait treats past actions like ongoing video footage or background scenery—things that were happening, continuing, or setting the scene without clear beginning or end points:

🇺🇸 Yesterday, I ate a pizza (passé composé—completed action, specific event)

🇺🇸 When I was little, I often ate pizzas (imparfait—habitual action, repeated over time)

English uses “ate” in both sentences, providing no grammatical clue about the distinction French requires. This is why English speakers struggle—we lack the mental categories French grammar demands, not because we’re bad at grammar but because English simply doesn’t make us think about past actions this way.

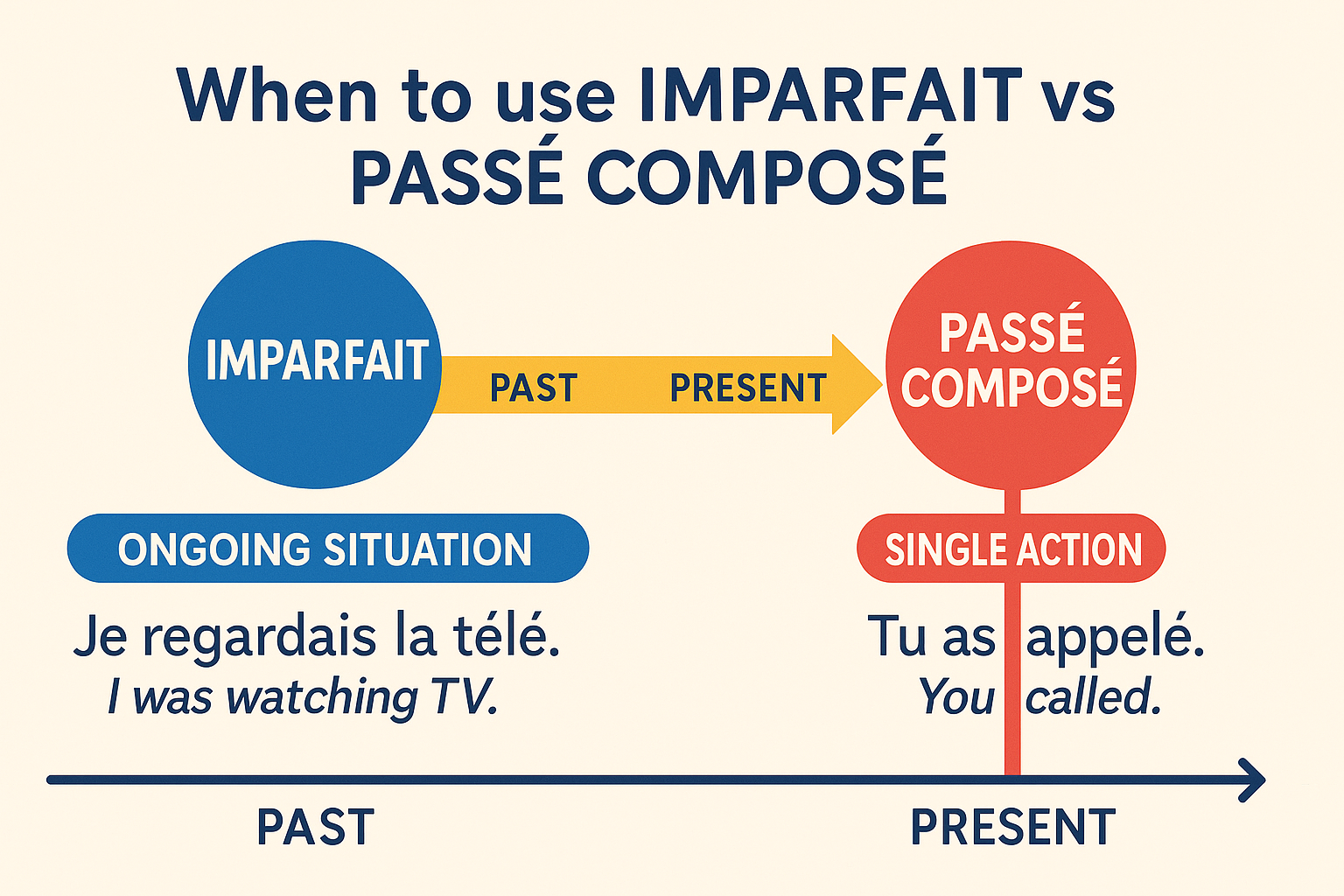

The timeline visualization: video versus snapshot

Roger’s breakthrough with imparfait versus passé composé came when a French linguistics professor taught him to visualize past narratives as movies. When you tell a story in French about the past, you’re essentially creating a mental movie with two layers: the background scenery and soundtrack (imparfait) and the specific events and actions that move the plot forward (passé composé).

Imagine describing a scene from a movie: “It was raining (background scenery—imparfait). The street was empty (background description—imparfait). Suddenly, a car appeared (specific event—passé composé). A man got out (specific action—passé composé). He was wearing a black coat (background description—imparfait).” In French, this narrative structure becomes automatic once you internalize the video versus snapshot distinction:

🇺🇸 It was raining. The street was empty. Suddenly, a car appeared. A man got out. He was wearing a black coat.

The timeline method Roger teaches in his lessons asks students to mentally draw a horizontal line representing time. Actions that create new moments on the timeline—things that happened and changed the situation—get passé composé. States, descriptions, and ongoing actions that fill the background of those timeline moments get imparfait. This visual metaphor makes the abstract grammatical distinction concrete and applicable.

Core Uses of Imparfait (Background/Ongoing/Habitual)

1. Descriptions in the Past (Physical and Mental States)

🇺🇸 The weather was nice (description of conditions)

🇺🇸 She was tall and blonde (physical description)

🇺🇸 I was happy (emotional/mental state)

2. Habitual/Repeated Actions in the Past

🇺🇸 When I was young, I played soccer every day (repeated habitual action)

🇺🇸 We always went to the beach in summer (regular repeated action)

3. Ongoing Actions in Progress (Background to Other Events)

🇺🇸 I was reading when you called (ongoing action interrupted by completed event)

🇺🇸 It was raining while we were walking (two ongoing simultaneous actions)

4. Time, Age, and Weather (Standard Descriptive Categories)

🇺🇸 It was eight o’clock (time statement)

🇺🇸 I was twenty years old (age description)

🇺🇸 It was snowing (weather description)

5. Verbs of Mental State/Emotion (Usually Imparfait)

🇺🇸 I thought that you would come (mental state)

🇺🇸 She wanted to leave (desire/wish as ongoing state)

🇺🇸 We hoped to succeed (hope as ongoing feeling)

The core uses of passé composé: completed specific events

While imparfait paints background scenery, passé composé delivers the action beats—the specific things that happened and changed the situation. These are the events you could list chronologically in a timeline, each one a discrete moment that occurred and concluded.

The mental test Roger teaches: can you answer “what happened next?” If the action moves the narrative forward to a new moment, it’s passé composé. If it describes the ongoing situation that existed during those moments, it’s imparfait:

🇺🇸 I opened the door (specific completed action—door is now open)

🇺🇸 She arrived at eight o’clock (specific completed event at specific time)

🇺🇸 We ate at the restaurant (completed action with clear endpoint)

Passé composé creates a sequence of events that build a narrative. You woke up, got dressed, ate breakfast, left the house—each action completes and leads to the next. This is the skeleton of the story, the plot points that move time forward. The grammatical structure of passé composé reinforces this completion concept through its two-part construction: auxiliary verb plus past participle, linguistically signaling that the action is finished, completed, done.

The interruption pattern: imparfait + quand + passé composé

One of the most reliable patterns for understanding the imparfait-passé composé relationship appears in sentences describing interrupted actions. When something ongoing (imparfait) gets interrupted by a sudden event (passé composé), French grammar makes this temporal relationship explicit:

🇺🇸 I was sleeping when the phone rang (ongoing background interrupted by completed event)

🇺🇸 We were watching TV when you arrived (ongoing action + interrupting event)

🇺🇸 It was raining when I went out (weather condition + specific action)

This pattern provides a mental hook: “quand” connecting two past actions almost always signals imparfait for the ongoing background action and passé composé for the interrupting event. English often uses past continuous (“was sleeping,” “were watching”) for the imparfait clause, which helps English speakers recognize the structure—though English can also use simple past without distinguishing the grammatical relationship French requires.

💡 Roger’s decision tree for choosing the right tense

Roger developed this step-by-step decision process in his lessons after watching students freeze mid-sentence, uncertain which tense to use:

Step 1: Ask “Is this a specific action that happened and finished?”

- YES → Probably passé composé

- Example: “I ate lunch” (specific completed action)

- Example: “She called me” (specific event that happened)

- Example: “We went to Paris” (trip that occurred and ended)

Step 2: Ask “Is this describing ongoing state, habit, or background?”

- YES → Probably imparfait

- Example: “It was cold” (ongoing weather condition)

- Example: “I used to play piano” (habitual repeated action)

- Example: “She was wearing a dress” (description of appearance)

Step 3: Check for time markers

- Imparfait signals: “toujours” (always), “souvent” (often), “chaque jour” (every day), “quand j’étais petit”

- Passé composé signals: “hier” (yesterday), “soudain” (suddenly), “à huit heures” (at 8 o’clock), “une fois” (once)

Step 4: The interruption test

- If one action was happening WHEN another action occurred → ongoing = imparfait, interrupting = passé composé

- Example: “I was reading (imparfait) when he arrived (passé composé)”

Step 5: Mental state verbs usually imparfait

- Verbs of thinking, feeling, wanting, knowing: “Je pensais”, “Elle voulait”, “Nous savions”

- UNLESS sudden realization or specific decision → then passé composé

Students who practice this decision tree daily for 2-3 weeks report that the choice becomes increasingly automatic.

Time markers that signal which tense to use

Certain French time expressions reliably signal whether you should use imparfait or passé composé, functioning as linguistic road signs that guide tense selection. Learning these markers helps you make correct choices even when the conceptual distinction feels unclear.

Markers that signal imparfait typically indicate repetition, habit, or ongoing duration without specific endpoints:

🇺🇸 Every day, I got up at seven o’clock (habitual repeated action)

🇺🇸 Usually, we went to the park (habitual action)

🇺🇸 In the past, people lived differently (general past state)

Markers that signal passé composé indicate specific times, sudden events, or counted occurrences:

🇺🇸 Yesterday, I saw Marie (specific day)

🇺🇸 Suddenly, it started to rain (sudden event)

🇺🇸 Once, I visited the Louvre (single counted occurrence)

The distinction between “tous les jours” (every day—habitual imparfait) and “un jour” (one day—specific passé composé) illustrates the pattern perfectly. Repeated actions use imparfait; single occurrences use passé composé, even if both happened in the past.

Essential Time Markers by Tense

Imparfait Time Markers (Habitual/Ongoing/Description)

- Tous les jours / chaque jour (every day)

- Toujours (always)

- Souvent (often)

- D’habitude / Habituellement (usually)

- Parfois (sometimes)

- Le lundi / le weekend (on Mondays / on weekends—habitual)

- Autrefois / À l’époque (in the past / in those days)

- Quand j’étais petit(e) (when I was little)

- Pendant que (while—for simultaneous ongoing actions)

Passé Composé Time Markers (Specific/Completed/Sudden)

- Hier (yesterday)

- La semaine dernière (last week)

- L’année dernière (last year)

- En 2020 / En mai (in 2020 / in May)

- À huit heures (at 8 o’clock)

- Soudain / Tout à coup (suddenly)

- Une fois / Deux fois (once / twice)

- D’abord… ensuite… puis… enfin (first… then… next… finally)

- Un jour (one day—specific)

⚠️ The “pendant” trap that catches everyone

“Pendant” (during/for) confuses English speakers because it can signal either tense depending on how it’s used, and English doesn’t distinguish these uses grammatically.

Pendant + time duration with completed action = Passé Composé:

🇺🇸 I lived in Paris for three years (completed period with clear endpoint)

🇺🇸 She worked for ten hours (completed work session)

Pendant que + ongoing simultaneous action = Imparfait:

🇺🇸 I was reading while she was cooking (two ongoing simultaneous actions)

The logic: “pendant trois ans” describes a completed period that has ended (you no longer live in Paris), so the action uses passé composé. “Pendant que” connects two actions happening at the same time without completion, so both use imparfait.

Roger’s rule: if you can replace “pendant” with “for” and the action is finished, use passé composé. If you can replace “pendant que” with “while” and both actions were ongoing, use imparfait for both.

Common errors and how to avoid them

English speakers make predictable mistakes with imparfait versus passé composé because English grammar doesn’t train us to make these distinctions. Roger identifies three patterns that account for probably 80% of errors his students make.

The first major error: using passé composé for everything because English simple past handles all past actions. Students tell entire stories in passé composé, creating grammatically incorrect French that sounds robotic to native speakers. The story “Yesterday I was tired, it was cold, I wanted to stay home but I had to go to work” becomes the incorrect “Hier j’ai été fatigué, il a fait froid, j’ai voulu rester chez moi mais j’ai dû aller au travail” instead of the correct “Hier j’étais fatigué, il faisait froid, je voulais rester chez moi mais j’ai dû aller au travail.”

The second major error: using imparfait for specific completed actions because students hear “description” and think any past narration counts as description. Saying “Hier j’allais au cinéma” when you mean “Yesterday I went to the cinema” (one specific trip) marks you as struggling with the tense distinction. The correct “Hier je suis allé au cinéma” uses passé composé because you’re describing a specific completed event.

The third major error: mixing up mental state verbs. Students correctly learn that mental states usually use imparfait but then incorrectly use imparfait even when describing a sudden realization or decision. Understanding when mental states shift from ongoing (imparfait) to completed thought (passé composé) requires nuanced judgment that develops with practice.

Study glossary – French past tense vocabulary

| French Term | English Translation | Usage Example |

|---|---|---|

| L’imparfait | Imperfect tense | On utilise l’imparfait pour les descriptions |

| Le passé composé | Compound past tense | Le passé composé exprime une action terminée |

| Une action terminée | A completed action | J’ai fini mes devoirs (action terminée) |

| Une action habituelle | A habitual action | Quand j’étais petit, je jouais (habitude) |

| Une description | A description | Il faisait beau (description) |

| Un état | A state | J’étais fatigué (état) |

| Soudain / Tout à coup | Suddenly | Soudain, il est arrivé |

| Tous les jours | Every day | Tous les jours, je me levais |

| Hier | Yesterday | Hier, j’ai vu Marie |

| Autrefois | In the past / Formerly | Autrefois, on voyageait différemment |

| Pendant que | While | Pendant qu’il dormait |

| Quand | When | Quand j’étais petit |

From confusion to automatic choice: building past tense fluency

The imparfait-passé composé distinction feels overwhelming initially because you’re learning two complete verb conjugation systems AND the conceptual framework for when to use each AND trying to apply both while speaking in real time. This cognitive load explains why the past tenses typically take 6-12 months of active practice to become automatic even for dedicated students.

Roger teaches a progression in his lessons that builds competence gradually. Start with recognizing the distinction in French you hear and read—notice when French speakers use imparfait versus passé composé without trying to produce both yourself yet. Then begin using passé composé for simple past narratives while keeping descriptions in present tense. Gradually add imparfait for clear habitual actions and obvious descriptions. Finally, practice the full integration where you naturally switch between tenses within the same narrative.

The timeline visualization method works because it gives you a concrete mental model rather than abstract grammar rules. When telling a story in French, literally imagine you’re directing a movie: background scenery, ongoing conditions, and repeated actions get imparfait—the video footage running continuously. Specific events that move the plot forward get passé composé—the snapshot moments that change what happens next. This visual metaphor becomes increasingly automatic with practice.

Native French children master this distinction by age 7-8 through thousands of hours of immersion. Adult learners using deliberate practice can achieve functional fluency in 3-6 months of focused study with continued refinement over the following year. The key is consistent practice telling past-tense narratives, getting correction, and internalizing the patterns through repetition rather than trying to consciously calculate every verb choice.

The moment you first tell a complete past-tense story in French—smoothly transitioning between imparfait descriptions and passé composé events without consciously thinking about the rules—you’ll know you’ve achieved the integration this grammar point demands. That automatic fluency comes from practice, mistakes, correction, and more practice, building the neural pathways that make grammatical choices feel intuitive rather than calculated.